What a stranded marine mammal can tell us about its environment

Every year, dozens of porpoises meet their ends on Belgian beaches. Scientists are trying to find the cause of death of these stranded cetaceans through autopsy. This provides valuable insights into the health of the North Sea.

‘A beautiful creature!’ Morphologist Pieter Cornillie is visibly excited about the autopsy of the porpoise that lies before us on a large stone table. ‘A female. The largest we’ve had here. Hardly any rigor mortis, so it’s very fresh, and intact. We can learn a lot from this.’

We are in the dissection room of the Pathology department of the Veterinary Medicine faculty of Ghent University. The porpoise is not the only creature that the vets-in-training will examine here today. Behind us, students are opening up the cadaver of a calf, and a farm horse weighing just under 1,000 kilograms is suspended by a hook over another table. The students performing the autopsy almost have to crawl inside the abdominal cavity of the impressive giant in order to study the stomach, intestines, lungs and other organs.

‘Dissections take place here every day of the week. Mostly of pets, horses and cattle brought in by individuals, cattle farmers or vets,’ says veterinary pathologist Koen Chiers, who invited me to attend the porpoise autopsy.

‘We’re trying to ascertain the cause of death. This information is useful to the animal’s owner or the vet, for example to prevent additional deaths from an infection circulating within a stable.’

‘The dissections of unusual animals also help us get a better idea of how animals look on the inside. This is of interest to veterinary medicine students, and also to us as scientists. There’s a lot we don’t know about the morphology of animals, the structure of their organs and tissue. Very occasionally we even perform an autopsy as part of a forensic examination, if an animal died in suspicious circumstances or was present during a crime.’

There’s a special guest on the slab today. ‘We hardly ever get a marine mammal here. That makes this autopsy particularly interesting.’ The porpoise is impressive. She has a chunky, grey-brown body and a short head with what looks like a friendly smile. The porpoise washed up four days ago on the beach at De Haan. Beachgoers kept the unfortunate creature wet while waiting for staff from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS) and the fire service. They are usually the first to be called upon when marine mammals are stranded. Sadly, the porpoise died during the rescue operation, an hour after she was found on the beach. The cadaver was immediately placed in a cold store before being brought to the dissection room in Ghent.

Once hunted, now protected

Porpoise strandings are no longer unusual these days. ‘In the 1990s, only a few porpoises a year would wash up along the Belgian coast. That suddenly became forty in 2003, and by 2016 almost 130. In recent years, we’ve counted almost a hundred each year,’ says Jan Haelters, marine mammal expert from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), who I spoke to ahead of the autopsy.

There’s a simple explanation for the increased number of porpoise beachings: there are a lot more porpoises in this part of the North Sea today. ‘In our area of the North Sea, less than 3,500 square kilometres, there are several thousand porpoises throughout the year. There are also around a hundred seals,’ says Haelters. ‘Oh, and a solitary bottlenose dolphin.’

In the mid-1990s, there was an unusual shift from north to south among porpoises. This probably had to do with food shortages in the north. Nesting birds, which are dependent on the same fish, also struggled during this period. It’s possible that those fish suffered in turn from a change in the availability of plankton due to climate change.’

This part of the North Sea is also inhabited by about a hundred seals and a solitary bottlenose dolphin.

Seals are also doing very well off the Belgian coast these days. ‘That’s a different story. Seals were once found in large numbers here. The grey seal disappeared back in the Middle Ages as a result of overhunting. The common seal disappeared during the twentieth century due to a combination of hunting, pollution and disturbance. They have been protected since the second half of the twentieth century, and the animals have gradually returned. First the common seal, then the larger grey seal. Now there are more grey seals in the North Sea than ever before and the population continues to grow. We’re waiting for it to balance out.’

‘Seals no longer have a natural enemy. Food supply and diseases will keep the population under control in the long term. And let’s hope that we’ll start seeing more natural predators, such as orcas,’ Haelters adds enthusiastically. (see box below)

Panic response

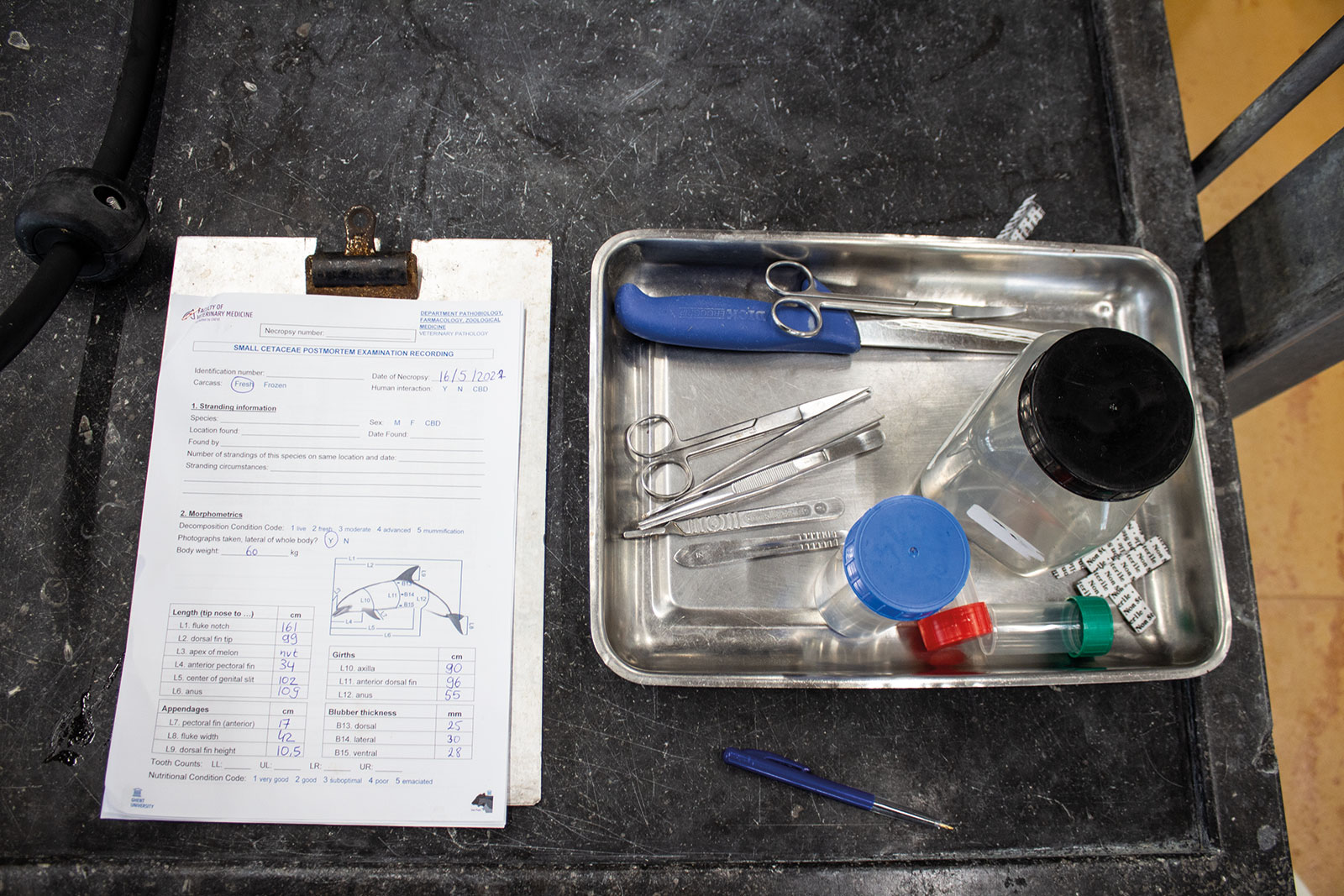

In the meantime, the porpoise autopsy has begun. The vets first record all the external characteristics on a form: 60 kilograms, 160 centimetres from nose to tail, female, and so on.

Koen Chiers points out a number of lateral lines on the porpoise’s left flank: ‘Scars from old lacerations. These can occur when porpoises are caught in fishing nets or even when they are attacked by grey seals. They may die immediately or from infection.

That’s not the case here. The wound has healed well, so that’s not the cause of death.’ The thickness of the layer of blubber doesn’t really help the examiners either. ‘This porpoise was well fed when it died. So the cause of death here may have been acute.’

‘Lactating mammary glands!’ These words from an observant student cause a sudden ripple of excitement around the dissection table. ‘So the porpoise is either pregnant or has recently given birth,’ says Pieter Cornillie. The latter seems to be the case, and very recently too. ‘We can establish that from the state of the womb. It’s likely that the calf was stillborn and the mother washed up during or soon after the birth.’

The lungs don’t reveal much about the potential cause of death. ‘If we find foam in the lungs, we can consider drowning in a fishing net,’ says Chiers. ‘That’s not the case with this animal.’ The researchers do find living, parasitic worms in the lung tissue. ‘But that’s actually normal in a living creature. Animals rarely die from that.’

The intestines and stomach (or stomachs, as porpoises have three) do tell the vets a little more about the creature’s final hours. ‘Completely empty! That’s a problem. Porpoises are warm-blooded creatures that live in a cold environment. Furthermore, their bodies are very compact, which means they have a large skin surface area in relation to their bodies through which they lose a lot of heat. They have to eat continuously in order to maintain their body temperature.’

The combination of a recent birth and an empty stomach might indicate stress, Chiers says. ‘Perhaps the mother panicked and eventually washed up, exhausted, on the beach. However, that’s an educated guess at best. We’re rarely able to determine the true cause of a beaching with 100% certainty.’

In the meantime, the porpoise has been almost completely ‘dismantled’. The students take a sample from each organ for further research. The tissue samples can be tested now or later for the presence of contaminating substances or infections. ‘Over the last ten years, we’ve seen more and more porpoises with viral brain infections,’ says Chiers. ‘Infections like this can cause death and therefore strandings. In order to examine the exact role of these viruses, we can study archived samples using advanced molecular techniques.’

Everyone can save the whales

This porpoise’s autopsy report will soon land on Haelters’ desk. ‘Strandings provide scientists and conservationists with important information on the biology and health of marine mammals. And, as they are at the top of the food pyramid, on the entire marine ecosystem.

Porpoises and seals are mammals. They are warm-blooded and eat fish, just like humans. ‘We can research the impact of contaminating substances on their health and draw conclusions regarding the risks for us of eating fish from the sea. Marine mammals eat much more fish than we do. So we can observe the effects much more quickly in them.’

In the 1970s, biologists established that seals struggled to reproduce due to the presence of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the water. ‘These substances are mainly used in industry, but they are also processed into plastics and adhesives,’ says Haelters.

The chemicals also ended up on our plates via contaminated fish. As a result, the manufacture and use of PCBs was banned. We’re seeing a similar story with plastics today. Pictures of seals tangled in plastic move people. They help to make people aware of the consequences of plastic pollution.’

The fact that our local marine mammals are doing well is sadly the exception. ‘Worldwide, it’s still not going well for the cetaceans,’ says a concerned Haelters. ‘Pollution, overfishing and increasing human activity still exert a great pressure on cetaceans large and small.’

Strandings provide scientists and conservationists with important information on the biology and health of marine mammals

‘In particular, the future of the arctic species such as the beluga or narwhal looks uncertain. The North Pole’s ice pack is shrinking. This enables orcas to hunt the relatively slow cetaceans. These species were safe in the past as the orcas, with their large dorsal fins, could not get beneath the ice. The beluga and narwhal are easy prey. They move extremely slowly. And as the ice disappears, shipping, fishing, tourism and fossil fuel exploration will increase. This will lead to more encounters with whales.

‘When people ask me what they, as individuals, can do to help whales, I say: consume less, so that there are fewer ships sailing around with stuff we don’t need. Eat less wild-caught fish and use fewer raw materials and plastic. Like this, we can all do our bit for these wonderful creatures.’

Sharks and orcas in the North Sea

In the Belgian part of the North Sea, there is a grand total of one bottlenose dolphin. Right up until the 1960s, there were estimated to be dozens if not hundreds of bottlenose dolphins in the southern North Sea. ‘It got too busy,’ says Jan Haelters (RBINS). ‘The dolphins became victims of pollution or overfishing.’

Nowadays, we see the odd one passing through and, occasionally, one stays for a few days, months or even years. There is a population of four hundred coastal bottlenose dolphins off the coast of Brittany. If that increases, there’s a chance that they’ll relocate to this part of the North Sea, but that might take time. I would not rule out the return of the bottlenose dolphins one day, but the omnipresent human activity makes it very difficult.’

‘The large whales that wash up here such as sperm whales or fin whales are not native, but lost. They miss a crucial turn around Great Britain. They swim around the bottom rather than around the top. The shallow waters mean there is a major risk that they will not make it. The humpback whale could feel at home here. There have been more and more sightings of humpback whales in the North Sea in recent years, possibly because the population as well as the food supply of sprat and herring is increasing. These stocks are always limited, by the way. There are sometimes claims in the media that fish stocks are healthy, but that’s not really true. They’re better than ten years ago but much worse than a hundred years ago.’

Slowly, seals have become abundant. This makes the arrival of two iconic sea predators more likely: the orca and the great white shark. ‘Seals are on the menu for both of these species. A great white has been spotted off the west coast of Britain – perhaps even two. And killer whales are regularly sighted off the west and north coasts of Scotland. There’s no reason to believe that the two species won’t eventually turn up here.’

This article first appeared in the Eos special issue about the North Sea.