Famous Ice Age ‘puppies’ likely wolf pups and not dogs

Two remarkably well-preserved Ice Age pups have been identified as wolf pups rather than early domesticated dogs, thanks to an international study involving researchers from the Institute of Natural Sciences. The so-called “Tumat Puppies,” discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2011 and 2015, were found with their skin and black fur intact, offering an exceptional glimpse into life more than 14,000 years ago.

The puppies were discovered in sediments frozen since the Ice Age, near the bones of woolly mammoths, some of which showed signs of having been burned and processed by humans. This led scientists to wonder if the site was once used by humans to butcher mammoths, and whether the puppies might have had a connection to people, possibly as early dogs or tamed wolves that hung around humans for food.

A new study, led by the University of York, however, has shown, based on genetic data from the animals’ gut contents and other chemical ‘fingerprints’ found in their bones, teeth and tissue, that the way they were living, what they were eating, and the environment they existed in, points to the puppies being wolf pups and not early domesticated dogs.

Sisters

The genetic analysis also proved that the pups were sisters. “The sister pair that was buried in a collapsed Ice Age wolf den was preserved with skin and hair,” says Mietje Germonpré, who is an archaeozoologist and expert on wolf domestication at the Institute of Natural Sciences and co-author of the study. “Their genetic features and the size of their teeth show that these puppies were wolves, not dogs.”

Anne Kathrine Runge, from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology, who analysed the pups as part of her PhD, said: “It was incredible to find two sisters from this era so well preserved, but even more incredible that we can now tell so much of their story, down to the last meal that they ate.”

Varied diet

The two pups were about two months old when they died. “From the presence of all their milk teeth and the tooth germs of their first molars, we could deduce that they were about two months old,” Germonpré explains. They were still drinking their mother’s milk, but had also started eating solid food—including a surprising item: skin from a woolly rhinoceros calf. One pup also ate a wagtail bird.

“By examining the contents of their stomachs, we were able to reconstruct their last meal,” she continues. Alongside animal remains, the pups had ingested plant material such as reedgrass, arctic bluegrass and willow leaves. “From this data, we were able to infer that they lived along the banks of a river or an oxbow lake; the climate at the time was dry and relatively mild.”

Black fur

The original hypothesis that the Tumat Puppies were dogs is also based on their black fur colour, which was believed to have been a mutation only present in dogs, but the Tumat Puppies challenge that hypothesis as they are not related to modern dogs.

Anne Kathrine added: “Whilst many will be disappointed that these animals are almost certainly wolves and not early domesticated dogs, they have helped us get closer to understanding the environment at the time, how these animals lived, and how remarkably similar wolves from more than 14,000 years ago are to modern day wolves.

“It also means that the mystery of how dogs evolved into the domestic pet we know today deepens, as one of our clues - the black fur colour - may have been a red herring given its presence in wolf pups from a population that is not related to domestic dogs.”

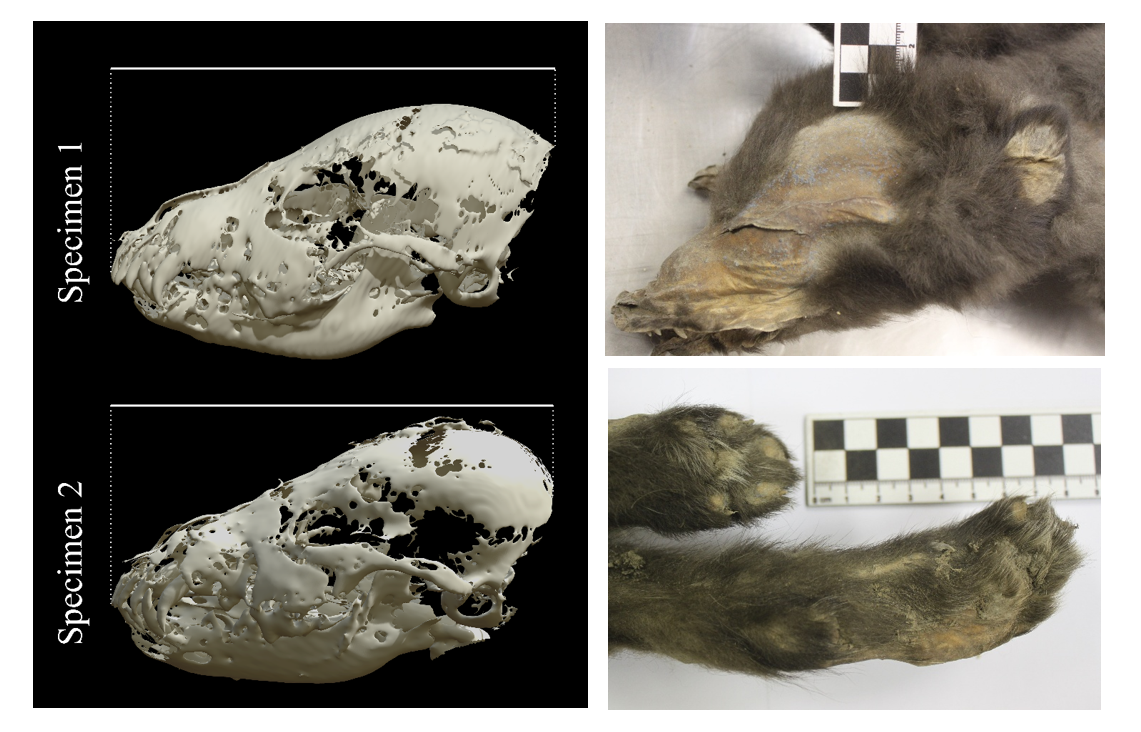

3D skulls

A key part of the anatomical analysis came from Jonathan Brecko, a researcher at the Institute of Natural Sciences. He created high-resolution 3D reconstructions of the pups’ skulls, allowing detailed comparisons with modern wolves and dogs. These models helped confirm the pups’ classification as wolves from a now-extinct lineage, not ancestors of domestic dogs.

The study, led by the University of York and including collaborators based in Belgium, Russia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, and Sweden, provides an unprecedented look into Ice Age ecosystems and the lives of ancient wolves. The research is published in Quaternary Research.

This article is based on a press release by the University of York.