Geologists assess natural disaster risks for European cities

A team of geologists has assessed the natural disaster risks for 41 European cities based on geological and climatic factors. Naples ranks highest, with Antwerp and Namur also making the top ten. "We aim to raise awareness among policymakers, urban planners, and residents about the ground beneath their feet so they can better anticipate the risks," the researchers say.

The floods in Valencia in 2024 and the ones in Wallonia in 2021 have underscored the devastating impact natural disasters can have on urban areas. But how vulnerable are European cities and metropolises to disasters such as floods, landslides, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions?

“The geology of a city is its first infrastructure,” explains Xavier Devleeschouwer, a geologist at the Institute for Natural Sciences. “It determines, along with climatic factors, the level of risk for natural disasters. If we fail to identify and address these threats, urban disasters will become even deadlier, especially as urban populations continue to grow. By 2050, an estimated 68% of the global population will live in cities, over 10% more than today.”

Led by ISPRA, Italy’s geological survey, a European team of geologists has developed the Urban Geo-climate Footprint (UGF) tool. This tool doesn’t calculate a city’s footprint, like the carbon footprint, but rather geological and climatic pressures upon that city.

The UGF tool visualizes and quantifies the geological factors that threaten cities, such as deep geological processes (earthquakes and tsunamis), surface-level processes (landslides or coastal erosion), and the impact of climate change on the subsurface. Using key factors, the tool provides a comprehensive risk score for each city, ranking the 41 cities tested so far.

Antwerp and Namur in focus

Naples tops the ranking with a score of over 315 (out of 500), primarily due to its location in an active volcanic zone near Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei. Additionally, its steep slopes increase landslide risks, and centuries of tuff extraction beneath the city have caused sinkholes.

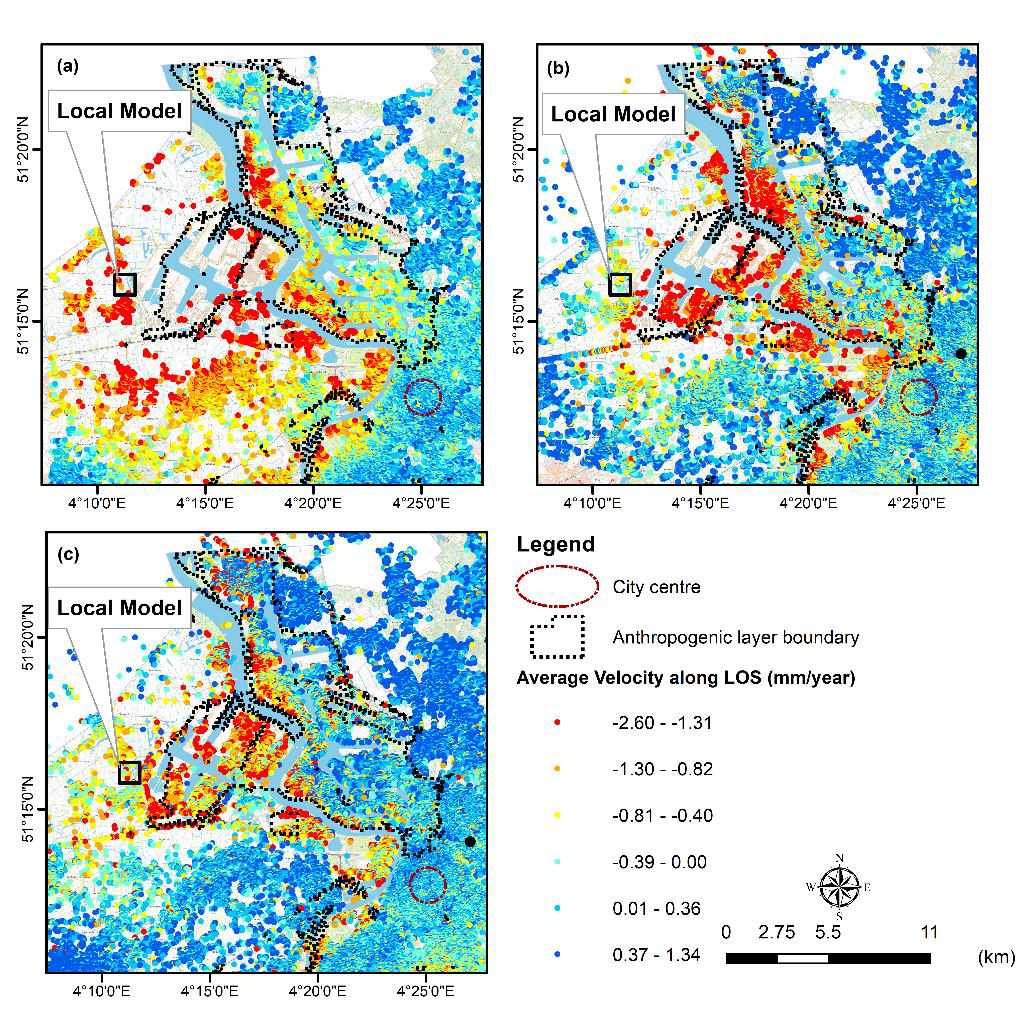

Antwerp ranks seventh with a score of 227. The city’s location in the Scheldt estuary is a major risk factor. Without dikes, parts of Antwerp in the polder areas would be highly vulnerable to flooding during high tides. “Over the last three decades, we’ve observed land subsidence along the embankments of the Scheldt river and some harbour facilities”, says Devleeschouwer. “The ground is sinking slowly because of natural river deposits from the last 12.000 years, which are covered by recent landfills. These layers of sediment and human-made landfills are being compressed, causing the ground to sink by 2.1 to 3.4 mm each year since 1992. However, the eastern bank, where the city center is located, remains stable. We will have to keep monitoring the underground, as climate changes and sea-level rise might also influence the natural phenomena and human-induced activities inside this area."

Namur ranks eighth with a score of 223. “Namur’s subsurface and the surroundings are highly diverse, rich in old coal mines, limestones, and old metals exploitations, and has been heavily exploited over decades,” Devleeschouwer explains. “Underground quarries, mine shafts, and galleries, even beneath residential areas, pose a risk for sinkholes. Mitigation resides on cartographic investigations based on mine documents and underground explorations to have an overview of ongoing stability issues.”

Brussels, meanwhile, falls into the category with the lowest risk. However, specific areas of the city still present challenges due to geological factors, specifically underground quarries and galleries. “In some areas the so-called ‘Lede stone’ was extracted, making the surface unstable.”

Encouraging collaboration

The researchers hope cities with similar risk profiles and challenges will collaborate. “We aim to inspire urban planners across cities to share ideas on preparing for threats and minimizing damage”, Devleeschouwer concludes.

The geologists published their study in the journal Cities and present their work in the mini-documentary Cities Under Pressure: