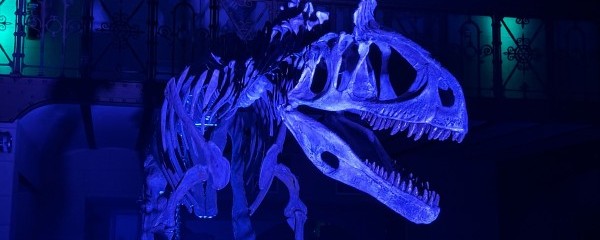

“Spiny dragon” reveals hidden secrets of dinosaur skin after 125 million years

An exceptionally well-preserved fossil from China reveals the true appearance and possible defence strategies of iguanodontian dinosaurs. The new species Haolong dongi preserves skin at cellular level and bears strange spikes never seen before in dinosaurs.

Although the genus Iguanodon celebrated its 200th anniversary in 2025 and remains one of the best-documented dinosaurs in the world, the broader group Iguanodontia still holds surprises. In a new study, an international research team describes Haolong dongi, a new iguanodontian dinosaur from northeastern China - preserved with skin so well fossilized that its cellular structure is still visible after 125 million years.

And the story also resonates closer to home: Haolong belongs to the same big family as the Bernissart Iguanodons - the stars of our Institute of Natural Sciences - offering a rare look at what the skin of their relatives could look like in life.

Skin preserved down to the cell nucleus

This juvenile dinosaur nicknamed the “spiny dragon” was not only armoured with large overlapping scales along its tail, but its body was also covered in spikes of different sizes - structures never before seen in dinosaurs. Advanced imaging and histological analyses revealed that these spikes were cornified and exceptionally preserved down to the level of individual keratinocyte nuclei. These appendages represent a unique evolutionary innovation, never observed in dinosaurs so far.

“Finding skin preserved at the cellular level in a dinosaur is extraordinary,” says Pascal Godefroit, senior author and palaeontologist at the Institute of Natural Sciences. “It gives us a window into the biology of these animals at a level that we never thought possible.”

What were the spikes for?

The spikes likely served as a deterrent against predators, making Haolong harder to swallow for the numerous smaller theropods that roamed the same ecosystem. They may also have played roles in thermoregulation or sensory perception.

“This discovery shows that even well-studied groups like iguanodontian dinosaurs can still surprise us,” adds Huang Jiandong, director of the research department of Anhui Geological Museum and first author of the paper. “The complexity of dinosaur skin is far greater than we imagined.”

Scale bars, 50 cm (A), 25 cm (B), 1 mm (C,D,F,H), 2 cm (E), 1 cm (G).

A new name in an iconic lineage

Named in honour of the late Dong Zhiming, a pioneer of Chinese dinosaur research, Haolong dongi occupies a basal position in the lineage leading to hadrosaurs - the famous duck-billed dinosaurs. Its unique integumentary structures highlight the evolutionary creativity of dinosaurs and underscore the importance of continued exploration.

“Two centuries after the naming of Iguanodon, we are still rewriting the story of these iconic herbivores,” says Wu Wenhao, co-author from Jilin University who first observed the presence of those bizarre structures in Haolong. “This fossil reminds us that nature’s experiments often leave behind spectacular traces.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Scale bars, 50 μm (a–c).