Skeletons of hundreds of Ice Age hyena cubs found in Belgian cave highlight severe ecological event that struck northern Europe about 45,000 years ago

Researchers from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, have recovered more than 300 skeletons of cave hyena cubs from a prehistoric cave in southern Belgium. The remarkable number of cub fossils suggests that the cave was regularly used as a birth den by cave hyena mothers, but also points towards a well-known phenomenon in nature: siblicide in times of food shortage and high competition.

A team of international researchers re-examined a collection of thousands of prehistoric fossil remains from the Marie-Jeanne cave located near Dinant, Belgium. The site was originally excavated in 1943 by a team of Belgian paleontologists and were more recently dated by radiocarbon methods in Oxford. Results show that the site accumulated between 47,000 and 43,000 years ago. No less than 15 different animal species were identified in this collection: horse, bison, woolly rhino, reindeer, as well as carnivore species such as wolf, cave bear, hyena and lion – a rather common faunal spectrum for that time period.

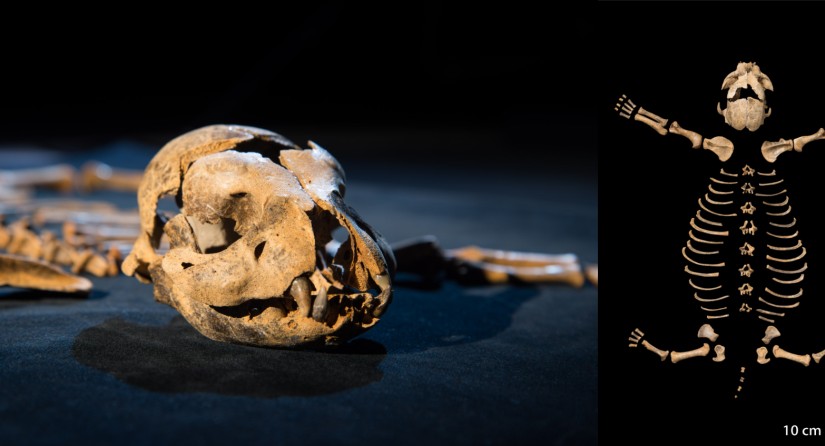

But something unusual caught the attention of the scientists. If cave hyena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea) was a common species found in the prehistoric ecosystems, archaeologists and paleontologists mostly recover adult individuals, sometimes associated with some younger individuals. At Marie-Jeanne cave, not less than 323 hyena cubs were identified – a large proportion of them only being a few weeks old.

For Elodie-Laure Jimenez, lead author of this study and archaeologist at RBINS and the University of Aberdeen, these fossils are an important paleontological discovery. "Whilst fossils of cave hyena are pretty common in prehistoric sites in Europe, the high concentration of newborn cubs here at Marie-Jeanne cave is a phenomenon never seen before on the fossil record... nor the modern one for that matter. It is pretty puzzling", she confesses.

Hyena behaviours in perspective

The cave hyena is an extinct subspecies of Crocuta crocuta, the modern spotted hyena living in sub-Saharan Africa. We know today that female hyenas isolate themselves from their clan to give birth in order to protect their offspring from aggressive interactions with fellow hyenas that could be detrimental to the lives of the youngling. Once the cubs have become stronger – oftentimes around 4-8 weeks – the mothers return to the clan with their litter, usually composed of two or three cubs

"The fact that only very few adult individuals were found at Marie-Jeanne Cave and that the majority of hyenas were only a few weeks old indicates that the site was not where the clan lived, but instead was mostly used as an isolated birth den by the mothers. And they did so for many, many generations!” says Jimenez. "This is an exceptional discovery because up until now, we knew very little about the social and reproductive behaviour of this key species of the Paleolithic ecosystem”.

Murder in the den

Since the number of cubs at Marie-Jeanne cave is far greater than what you find in any other palaeo-sites – not even in modern spotted hyena dens – the researchers suspect that an unexpected phenomenon occurred in this region at that time. “During periods of strong ecological pressures and prey depletion in the local environment, the weakest of the siblings end up being killed by the dominant, who then gets access to more maternal resources”, explains Jimenez. “This usually occurs when the mother has to travel longer distances in search of prey and has to leave the cubs behind for longer periods of time”.

During this period of the last “Ice Age”, sub-arctic climatic conditions struck northern Europe and many species had to adapt their behaviour to survive. In the northern latitudes (Great-Britain, Belgium, and “Doggerland”, the vast plains that are now under water in the English channel) our ancestors the Neanderthals largely relied on big herbivores such as bison, woolly rhino or mammoth to get enough fat, proteins and clothing material. Therefore they were sometimes in high competition with other large predators like cave hyenas and both had to adapt their strategies by migrating long distances or hunting different species.

Humans vs carnivores

Identified for the first time by the British geologist William Buckland in 1823, the cave hyena populated the whole of Eurasia until its disappearance in Siberia, about 14,000 years ago. Due to its odd silhouette and scary “laugh”, the hyena is an animal that is not very present in our social imaginary. However, it was an essential large carnivore of the prehistoric ecosystems in which it played an essential role in maintaining its balance.

The new knowledge generated by this unique discovery and ongoing analyses will allow us to better understand the dynamics between prehistoric human species and large carnivores in northern Europe and how they adapted to the climatic variations of the Ice Age. It’s important to note that the Neanderthals disappeared from our northern latitudes just a few millennia later - around 40,000 years ago – after Homo sapiens had arrived in Western Europe. A combination of various ecological pressures then triggered the “Quaternary mass extinction”, from 35,000 to 10,000 before present, during which most of the mammals weighing over 40kg got extinct.

The study has been published in the Journal of Quaternary Science.