Amateur paleontologists donate rich collection of fossil shark and ray teeth to our Institute

Citizen scientists have donated tens of thousands of fossil shark and ray teeth to the Institute. They were excavated at the clay quarry of Egem in West Flanders, and bear witness to the rich diversity in the shallow tropical sea around 50 million years ago in our regions. The amateur paleontologists were able to identify more than sixty different species of sharks and rays, including some new species of rays.

For over thirty years, professional paleontologists and enthusiasts have combed the clay quarry in Egem (Pittem) for fossils. The site, dating back to the early Eocene (about 50 million years ago), is well-known in the field and has already yielded publications on plankton, squids, crabs, bony fish, birds, and land mammals that lived along the coastline at that time. This provides insight into the ecosystems in that distant past.

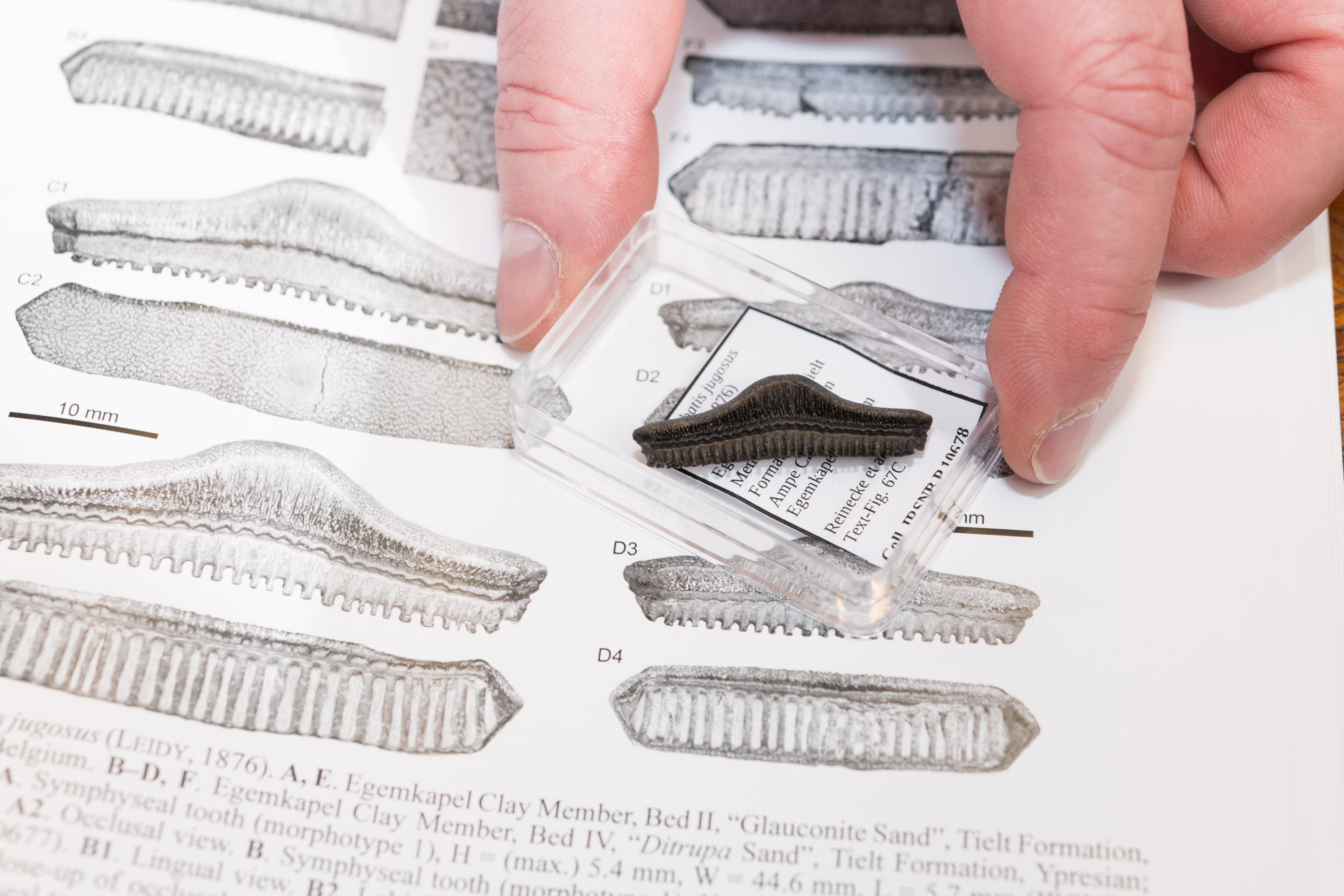

Fossil collectors found mainly teeth of sharks and rays in Egem because these fish constantly replace their teeth throughout their lives. "For the description of species, we have to rely on the teeth, as their cartilage skeletons are rarely preserved," says Frederik Mollen of the Flemish Research Group for Sharks and Rays.

Based on these numerous teeth, they were able to describe new species of rays, such as eagle rays and sting rays. "Each species has its own eating habits and corresponding tooth shapes. Eagle rays have flattened teeth, which they use to easily crack shells. The giant manta ray, on the other hand, simply eats plankton." One new species of ray is named after Theo Lambrechts, one of the enthusiasts who spent a part of his life sieving and studying the material from Egem.

Other amateur paleontologists (see photo) are also donating their most important specimens to the Institute - totaling tens of thousands of fossils - after they have been extensively documented in a monograph.

Unique circumstances

"Egem is an exceptional site," says Thomas Reinecke, a German geologist who went excavating there about fifteen times. "Due to local conditions in the early Eocene, a large number of fossil teeth accumulated here. When I stuck my tools into the clay and heard a crack, I knew: teeth!"

The mainly small fossils will be added to our paleontological collections, and the most important specimens will be digitized. This will further unlock them for research. The Institute of Natural Sciences preserves more than three million fossils, from the early periods of complex life to the last ice age, and from nanofossils to the Iguanodons of Bernissart.