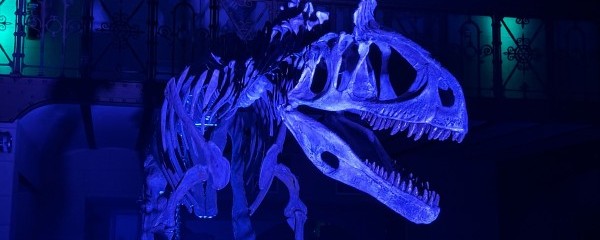

Mating injuries as clues to recognize female dinosaurs

Paleontologists have discovered a striking pattern of fractures in the tail vertebrae of duck-billed dinosaurs, which may have occurred during mating. “The weight of the male could have crushed the female’s back,” says Filippo Bertozzo of the Institute of Natural Sciences, first author of the study. “These injuries may help us identify female dinosaurs.”

A new study by an international team of paleontologists led by Dr. Filippo Bertozzo of the Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels (Belgium), describes a series of traumatic bone lesions in the tails of one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs, the herbivorous “duckbilled” hadrosaurids.

“Duckbilled” dinosaurs, like trumpet-like crested Parasaurolophus (famous from the movies, Jurassic Park and Jurassic World) and the massive Edmontosaurus, roamed the planet during the Late Cretaceous Period, shortly before the notorious K-Pg mass extinction event. Fossilized bones of hadrosaurs have been found worldwide, making them one of the most intensively studied groups of dinosaurs.

Previous research on hadrosaur pathologies has found a multitude of injuries and diseases. From trauma to infections, tumors to developmental disorders, the skeletons of hadrosaurid dinosaurs clearly show that life in the Cretaceous was indeed harsh, with a constant fight for survival.

c) Filippo Bertozzo/iScience

Healing fractures

In 2019, during a research visit to Blagoveschensk, Russia, Bertozzo was studying a large hadrosaurid with an ornate fancy head crest, Olorotitan arharensis. He noticed that many of the Olorotitan’s tail vertebrae showed healing fractures on their spines. “I was puzzled by that observation”, Bertozzo says. “I have seen this pattern in other similar species, but only in isolated vertebrae. Here, the fractures were visibly concentrated in the vertebrae at the upper end of the tail, without extending down to its tip”.

Bertozzo studied duckbill dinosaur pathologies for his Ph.D. research at Queen’s University Belfast, under the supervision of Prof. Eileen Murphy and Dr. Alastair Ruffell, co-authors of today’s study. “It is indeed a peculiar situation” Murphy says, “often when you find a caudal vertebra from the upper end of a hadrosaur tail, there is a strong chance of it bearing a healing injury. This is a clear pattern, and we set out to try to explain its cause.

Mating hypothesis

Since 1979, co-author Darren H. Tanke has been collecting hadrosaurid remains from Dinosaur Provincial Park (Alberta, Canada), including several injured caudal tail vertebrae. These discoveries led him in 1989 to formulate an idea to explain this strange pathological pattern. “In contrast to other dinosaurs, hadrosaurids show fractured tail vertebrae in an area close to the likely location of the cloaca”, Tanke affirms. “This led me to propose the idea that these injuries were inadvertently caused during mating”.

Unfortunately, Tanke’s observation was based on a limited number of specimens and species, all from North America. Even though it was fascinating, his hypothesis could not stand up to scientific scrutiny at the time. That was until Bertozzo contacted him in 2019 and invited him to collaborate on the project. “Darren is the father of this hypothesis” Bertozzo tell us that “I cannot forget the look of surprise on his face when I told him I had discovered the same pattern in other hadrosaur remains outside Canada”.

Downward pressure

The new study is based on about 500 pathological tail vertebrae from different hadrosaur species from North America, Europe and Russia. The appearance of the backbone injuries is strikingly similar between species, showing a vertical-to-oblique injury, likely caused by vertical pressure having been placed on the tip of the vertebral spinous process.

A statistical analysis on the dataset was paired with Finite Element Analysis, an engineering technique that predicts how a structure behaves under mechanical stress, in this case by bending or fracturing. The results showed that the fractures were consistent with a pressing force acting externally from above, at about 60-to-30 degrees, causing stress which resulted in fractures on the elongated spines of the tail vertebrae.

Complex reproductive behaviour

“Once we obtained the results, we had to consider every scenario”, said co-author Simone Conti, “from predation to muscular stress during locomotion, from herding accidents to even rare and unusual behaviors such as mud wallowing, as observed in modern elephants. At the end, the mating hypothesis was the one that correlated best with our observations”.

Under this hypothesis, the weight of the male presses on the upper part of the tail of the female, causing the bone stress fractures. These injuries were not fatal, however, as many specimens have injuries with signs of healing. In some cases, the bones even displayed evidence of a second injury indicating repeated behavior!

“Aggressively pursuing a female during reproduction might sound evolutionary disadvantageous for the continuation of the species”, says co-author Prof. Gareth Arnott, “but we already witness similar occurrences in many modern species, such as in sea lions, turtles, and some species of birds. Reproductive competition is one of the most complicated topics in animal biology, especially for extinct species”.

Female dinosaurs

These new findings are not the final word on this surprising aspect of dinosaur life. Instead, it is the authors’ hope that they will inspire further research. “If the mating hypothesis is correct” Bertozzo says, “we can infer that an individual with the injuries is female. This will be a game changer since it will enable other questions to be answered about differences between male and female dinosaurs. Did they have differently shaped skulls? Can we discover sexually dimorphic features that will help us understand the social structure of an hadrosaur herd?”

Further development of this study on a wider dataset which includes different dinosaur clades, and the use of additional computer simulations has the potential to enable us to gain an even greater understanding of the lives of these long dead animals.

The study was published in the scientific journal iScience.