A fossil provides oldest evidence of plant self-defence in wood

Paleobotanists have found fossils in Ireland showing that plants had adapted to drought very early on.

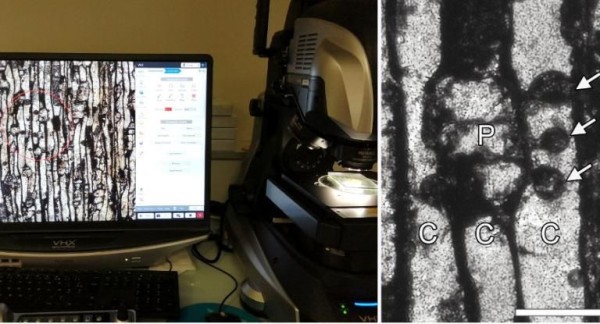

Plants can protect their wood from the spread of air bubbles (embolism) and pathogens by forming structures called "tyloses". Such structures have now been discovered by an international team in fossil wood dating back to the end of the Devonian, some 360 million years ago.

The discovery - on which researchers from the University of Liège and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences collaborated - appears in the journal Nature Plants. It provides a better understanding of the evolutionary history of this defence mechanism and the biology of the first woody trees.

Protection against drought

The fossil record is an invaluable source of information about past ecosystems. Sometimes even a tiny detail can reveal important aspects of the ecology of an entire organism and its ecosystem. This is what happened to a team of Belgian, French, Irish and German researchers, who had uncovered a very elaborate drought protection mechanism in plants dating back to the Devonian period (360 million years ago) that they had collected in south-eastern Ireland. This phenomenon, known as tylosis, which can completely block certain conductive cells and thus protect the rest of the wood from the propagation of pathogens (fungi, for example) or air bubbles.

Cyrille Prestianni, palaeobotanist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and the EDDyLab at ULiège, helped collect, date and study specimens of Callixylon, the fossil plant that was studied. Callixylon is particularly important because it is part of the now extinct group (the archaeopteridales), which was one of the first groups to form large trees in the Devonian. These plants reproduced by spores - like ferns today - but produced wood resembling that of the gymnosperms (a sub-branch, nowadays almost exclusively formed by the conifers: pines, cypresses, junipers, etc.)

Avoiding worse

By studying the structure of this wood in detail, the researchers identified those unusual structures, tyloses. These are outgrowths of 'parenchyma cells' (one of the cell types that form plant tissue) that extend into an adjacent aquifer cell. This means that the plant was able to block its vascular system. This can be vital for a plant if air bubbles form during droughts that can spread through the vascular system, like an embolism. Too many clogged ducts can cause the tree to die.

In this way, these first tall trees were already able to survive periods of drought. At the transition from Devonian to Carboniferous, the second mass extinction occurred on our planet. Although the causes and the effects are not yet known, it is clear that marine life suffered enormously. This research project is now trying to find out to what extent the extinction was also felt on land.

These are details of how the oldest forests functioned

- Cyrille Prestianni (Institute of Natural Sciences) -

"This discovery is exceptional in several ways. Firstly, because of the remarkable level of preservation of the fossil and the degree of detail that is observed. Secondly, because of the fact that the authors are highlighting details of the functioning of the oldest forests known to the earth", explains Cyrille Prestianni. This study thus illustrates how fossils can provide detailed information about certain physiological processes that are even hundreds of millions of years old. This type of information allows us to understand fossil plants as once-living organisms and to trace the deep origin of key biological processes that still exist today.