A 400-million-year-old placoderm reveals how the first dentitions were structured

A placoderm species from Canada that lived some 400 million years ago offers us a glimpse into the very earliest beginnings of tooth evolution: dental plates attached to the palate with small teeth that grew in all directions. "This is an organisational model that we didn't know about and which could correspond to the ancestral model of all jawed vertebrates," declares palaeontologist Sébastien Olive from the Institute of Natural Sciences and the University of Liège.

To understand tooth evolution, we must go back to the beginning of the Devonian period, about 400 million years ago, when North America and Europe still formed a single continent located just below the equator. In practically all the oceans of that time swam armoured fish, in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Armoured fish or placoderms constitute the extinct sister group of cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays) and bony fish (all other fish, including tetrapods of which we are part). The head and thorax of armoured fish were typically covered with bony plates. Dunkleosteus is perhaps the most iconic: about four metres long and a super-predator at that time. Placoderms are the first vertebrates to have developed jaws.

It was long thought that placoderms had no teeth on their jaws, and that teeth had evolved much later. But since 2012, palaeontologists have found true teeth in different groups of placoderms. Jaws and teeth would therefore have developed approximately at the same time.

Placoderm teeth

But how do these teeth grow? A 2020 study had concluded that new placoderm teeth, present on different cheek bones, always appeared at the back of the mouth, thus giving a row of worn teeth at the front and intact ones at the back. These growth patterns also correspond to what we find in cartilaginous and bony fish, and it was therefore suggested that this pattern would be at the basis of all jawed animals. But the new study, on an armoured fish from Canada, now contests this: the teeth didn't grow only from the back but in all directions, and not only on cheek bones but also on bony plates attached to the palate. It's a strange dentition that brings new information about the evolutionary history of teeth and their development.

These are the conclusions reached by an international research team including palaeontologist Sébastien Olive (Institute of Natural Sciences, University of Liège). They analysed the fossil remains of a placoderm that was found in 1995 by a Franco-Canadian team on Prince of Wales Island, in northern Canada. It's a new species, named Romundina gagnieri.

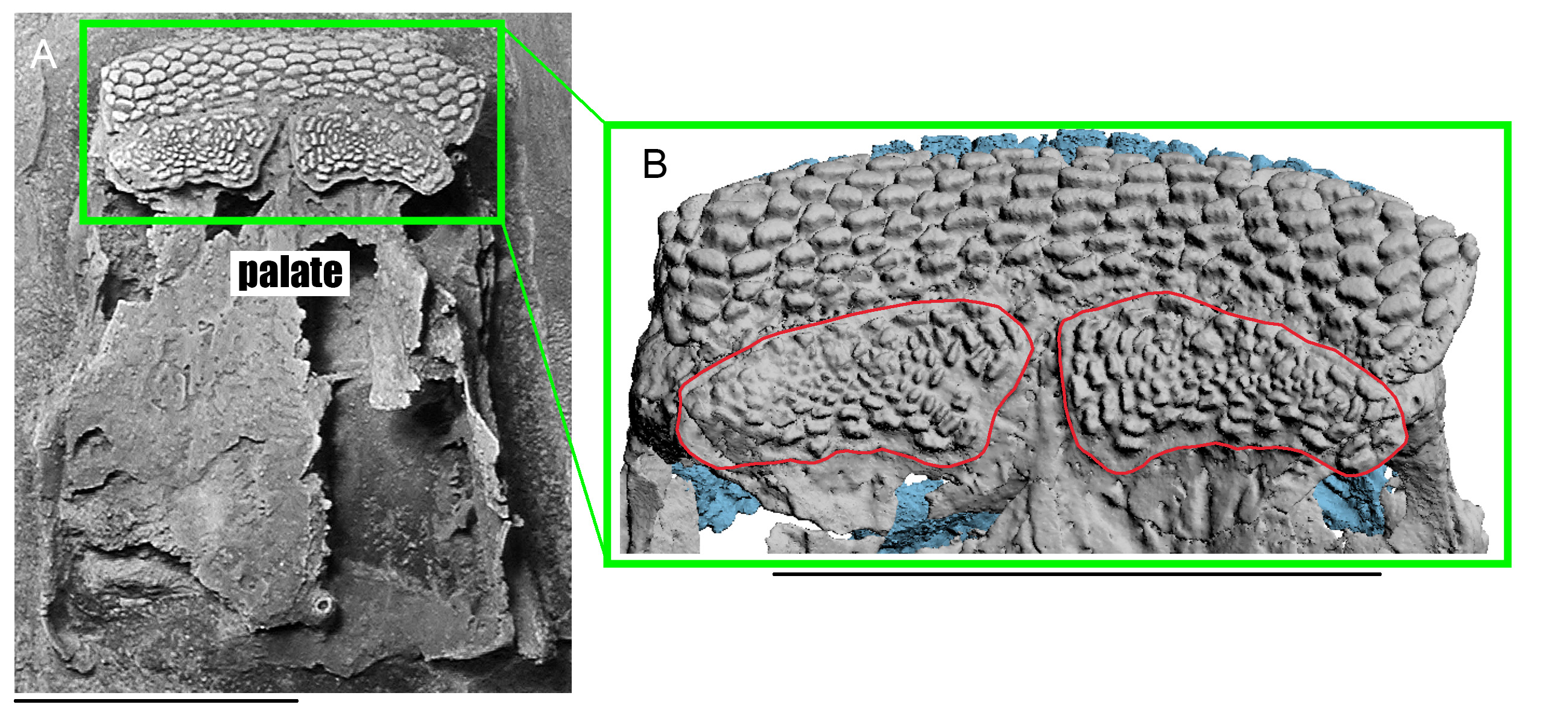

The specimen was scanned from all angles by X-rays in a synchrotron in Switzerland, then a 3D model was created. It's an interesting technique for looking inside a specimen without having to break it. The palaeontologists conclude that the teeth grew on bony plates attached to the palate and following a circular pattern, comparable to tree rings. The teeth that grew first were located in the centre and the following ones around them. The synchrotron analysis even made it possible to highlight other mineralised structures (whose origin is unknown) that came to cover some of the teeth and that probably helped the animal during its lifetime to crush very hard foods.

A decisive change

The studied specimen belongs to a group of placoderms called acanthothoracids. It's interesting to note that the same dental organisation was also found in another group of placoderms, the arthrodires, a group to which the iconic Dunkleosteus also belongs. We can therefore formulate the hypothesis that the common ancestor of the two groups of placoderms probably also had such a dental apparatus in the mouth.

"We are looking here at one of the first steps in tooth evolution," says Sébastien Olive. "Armoured fish are not only the first vertebrates to have jaws, they are also the first vertebrates to show different patterns of dental organisation. Biting and chewing with teeth was a game changer. This allowed our distant ancestors to exploit new food sources and occupy new ecological resources."

The study is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.