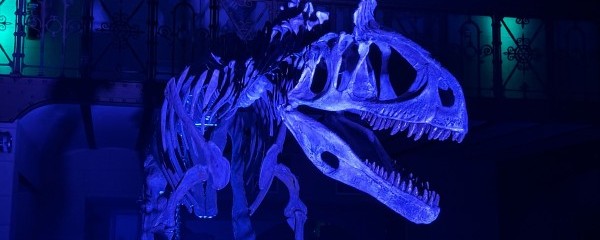

Newly described Shri rapax hunted with stronger hands than cousin Velociraptor

Step aside, Velociraptor — here comes Shri rapax! This newly described predatory dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia had powerful hands and an exceptionally long claw, allowing it to tackle larger prey than other raptors living in the same desert.

One hundred years after American paleontologist Henry F. Osborn described the iconic Velociraptor mongoliensis, an international team of paleontologists presents a “cousin” of the small iconic predator. And it comes from the same Djadokhta Formation in Mongolia. These geological layers reflect a Gobi-like desert dotted with lakes some 75 to 71 million years ago (Late Cretaceous).

Stronger Hands, Longer Claw

“This suggests that Shri rapax was specialized in hunting larger or harder-to-catch prey than its close relatives.” What it ate exactly is uncertain. “We suspect Protoceratops, a dinosaur with a large neck frill, and juvenile specimens of the armored Pinacosaurus. Many fossils of these herbivores have been found in the same geological layers.” One famous find shows a Velociraptor and Protoceratops that died during a fight, known as the “Fighting Dinosaurs”. For Shri rapax, the small and slow Protoceratops would certainly have been an achievable target. They may have hunted in groups, although there is no evidence for that yet.

Divide and Coexist

The more robust arms and hands of Shri rapax suggest a different attack technique. “With its powerful arms and hands, it could hold onto prey tightly, then finish it off with repeated strong bites. Velociraptor likely attacked prey first with its feet and sickle-shaped toe claw before using its teeth.”

The anatomical differences between Shri rapax and its closely related contemporaries suggest that the dromaeosaurid group was ecologically diverse. “These species lived in the same landscape but developed different specializations. They occupied different ecological niches and could therefore coexist perfectly.”

The specimen was likely buried by a collapsing dune. The posture — curled up with neck and tail raised — is typical of vertebrates that suffocated or drowned

Although no feather traces were found on the skeleton, Shri rapax likely had feathers. “Soft tissues like feathers don’t preserve in these Mongolian sediments. But in slightly older layers in China, small raptors have been found that were fully feathered, with wings on both forelimbs and hindlimbs. And on a Velociraptor from the Djadokhta Formation, small bumps were found on the forelimbs — typical attachment points for feathers. So we’re almost certain Shri rapax had feathers and resembled a large turkey. This family of raptors, the dromaeosaurids, is the closest relative of modern birds.

The fossil skeleton of Shri rapax is “articulated”: the fossil bones fit together nicely. The tail is especially well preserved, with its sheath of ossified tendons and joint projections that gave the tail stiffness and helped the animal maintain balance. Godefroit: “The specimen was fossilized in the position in which it died. It was likely buried by a collapsing dune. The posture — curled up with neck and tail raised — is typical of vertebrates that suffocated or drowned. Many specimens of the Bernissart Iguanodons were found in similar positions.”

From Illegal to Official

The fossil skeleton of Shri rapax has a turbulent history. It was poached, smuggled out of Mongolia, and sold on the black market. Finds on Mongolian territory legally belong to the state. After being resold by private owners in Japan and Europe, it ended up with the French fossil company Eldonia. Eldonia reported the specimen to the Institute of Natural Sciences, which had the skull 3D scanned in 2016 for initial research. “Good thing we did, because the skull was later lost after returning to France,” Godefroit laments. “Thanks to the scans, we were still able to describe the skull scientifically and make a cast.”

Paleontologists must stay alert and try to convince private owners to donate interesting pieces to science and make them publicly accessible

After negotiations between Eldonia, paleontologists, and Mongolia’s Ministry of Culture, the fossil skeleton is now officially being returned to its country of origin. A few years ago, Halszkaraptor escuilliei — the swimming raptor — from the same Djadokhta Formation followed a similar path: from illegal merchandise on the black market to return to Mongolia after intervention by paleontologists.

“It’s a sad reality that illegal excavations happen. But the black market and private circuit exist, and exceptional specimens circulate within them. So paleontologists must stay alert and try to convince owners to donate interesting pieces to science and make them publicly accessible.”

The study is published in the journal Historical Biology.